Peru

According to official information, in the Callería district, deforestation due to illegal coca leaf crops was around 900 hectares in 2019. About 30% is concentrated in the Abujao basin, according to the Institute for the Common Good (IBC). Image: Sebastián Castañeda / Mongabay Latam.

Pucallpa-Cruzeiro do Sul:

The highway that could trigger violence in Ucayali

Authors: Alexa Vélez / Vanessa Romo

Field collaboration: Ítalo García

Photographs and videos: Sebastián Castañeda

The sun was setting on the Abujao River near the border between Peru and Brazil when the boat of indigenous leader Jorge Pérez ran out of fuel. It was 5 o'clock in the afternoon last November and he only had to row to the nearest town to continue his journey to Pucallpa, capital of the Amazonian region of Ucayali in Peru, the next day. When the tip of his boat touched the shore, four people, young and old, stepped out of the bushes.

-Who are you? I've never seen you before, said one of the younger ones.

-I live here. I think you are mistaken. It's the first time I've seen you, actually, replied the indigenous leader with the firmness of someone who has been traveling along the Abujao River for more than 20 years.

Pérez realized the danger he faced when he saw that the four were carrying rifles. He glanced up and saw that there were 20 other people in the brush. "I am not the only villager to whom something like this has happened, but since all these people are outsiders, they are always checking to see if you are a policeman," says the indigenous leader, who for security reasons asks us to protect his name. In the last five years, the presence of migrants from Ayacucho and Apurímac along the Abujao river, in the district of Callería, has increased, and the invasion of Ashaninka and Shipiba indigenous lands has also grown.

One of the problems that most worries the inhabitants of Abujao is the disappearance of the wildlife. Contrary to other years, fishing is no longer the same. Photo: Sebastián Castañeda/Mongabay Latam

Why was Jorge Pérez approached by this armed group? At first, he was not sure who he was dealing with, but his suspicions were confirmed the next day when, at 5 in the morning, he heard the constant sound of light aircraft in the area. Although the presence of illicit coca crops in Abujao dates back some 20 years, the residents interviewed for this report confirm that in the last five years the area has become a "red zone", as they call the place where groups linked to drug trafficking, specifically cocaine paste, operate. Their testimonies are confirmed in the reports of the National Commission for Development and Life without Drugs (DEVIDA).

But there is another threat to this region of the Peruvian Amazon: the construction of the Pucallpa-Cruzeiro Do Sul highway, a highway project that seeks to commercially connect Peru and Brazil. This interconnection inevitably evokes the ghost of the Interoceanic Highway, one of the most expensive road projects in Peru - built by the Brazilian company Odebrecht, implicated in an investigation for the payment of bribes to Peruvian state officials - which was intended to connect both countries and which has meant the loss of at least 437,000 acres of primary forests, according to the report of the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP).

The proposed Pucallpa-Cruzeiro Do Sul highway - which was unveiled in 2003 - has already been the subject of studies, analysis and criticism by scientists, indigenous organizations and environmental groups. The last proposed route for this road runs parallel to the Abujao river basin and crosses at least ten Shipibo and Asháninka indigenous communities such as Bethel, Betania, Santa Rosita de Abujao and San Mateo, located on the border with Brazil. Also, according to experts consulted by Stories Without Borders, this stretch of road would cut through a biodiversity corridor that begins in the Sierra del Divisor National Park and the Isconahua Indigenous Reserve and ends on the other side of what would be this road, in the zone of influence of the proposed Alto Tamaya - Abujao Regional Conservation Area (ACR).

In this figure we can see three important variables: the location of the indigenous communities, all of which live along the river; the proposed route of the Pucallpa - Cruzeiro Do Sul highway; and the patches of deforestation caused by coca. The fear is that these patches will grow larger with the presence of a major road. This map was prepared by the University of Richmond and the Institute for the Common Good at the request of Mongabay Latam.

Opposition to the project has not prevented it from being reactivated from time to time. This time it is because of the interests of regional authorities of Ucayali, such as Governor Francisco Pezo Torres, and of Acre, the latter in Brazil. Then too, there’s the Peruvian Congress, where a parliamentarian from Ucayali has presented a bill to declare the road of national interest. On the Brazilian side, interest in this road has grown with the arrival of Jair Bolsonaro to the presidency in 2019. After 18 years, nothing stands in the way of the progress of this project -- despite the fact that a 2020 study by the Conservation Strategy Fund estimates that the new road would cause the deforestation of almost 60,000 acres of forest on the Peruvian side, and an economic loss of $17 million.

The regional governor of Ucayali, Francisco Pezo Torres, has assured Stories Without Borders that the idea of building a road comes from the Brazilian authorities and that he is looking for an air or rail connection as a first choice. However, the idea of a highway has not yet been officially ruled out. Why push for a road despite the environmental risk and the significant presence of drug trafficking?

The Brazilian connection

The first time the road was mentioned was in 2003, when the Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America (IIRSA) was being designed. At that time, in Cruzeiro Do Sul, regional authorities from Peru and Brazil signed an agreement to promote a connection between the two countries. A year later, agreements were still being signed, including one that would promote Brazilian meat exports and Peruvian vegetable exports. As plans grew, the highway proposal gained ground.

Nature continues to make its way in the midst of the heavy deforestation the area has experienced in the past decade. Photo: Sebastián Castañeda/Mongabay Latam

On the Peruvian side, up to three different sections were being developed, some of which contemplated crossing the Sierra del Divisor National Park or the Isconahua Territorial Reserve - home to indigenous people in voluntary isolation. The Regional Government of Ucayali decided to wait for technical studies to evaluate the best route. Seven years later, Provias Nacional launched a call for a pre-investment study. This was approved in 2013 and the section that runs parallel to the Abujao River prevailed. Administratively, this was the last chapter of the road.

During those years, the federations and indigenous communities remember the rumors that circulated about the probable construction of a road. Edgar, an inhabitant of the Santa Rosa Native Community, says they could not stop thinking about how the road would affect their lives.

"The contamination is going to arrive, there will be no more animals or fish and we live off that,” says the leader of the Shipiba community of Santa Rosa. That is what they were thinking in those days, while they waited in vain for authorities to give them information about the project. A few months later, the ghost of the road vanished. But not for long. "We had forgotten about the road and recently we heard about it again," says the indigenous leader.

Luis Dávalos, a specialist at The Nature Conservancy, an environmental organization that has worked with other institutions to analyze the possible impacts of the highway, explains that the project "has not advanced in technical terms, but there are advances in political terms, mainly promoted by Brazil”.

Along the Abujao River, five hours away from Pucallpa, groups of settlers have appeared in the last ten years and have expanded the agricultural frontier. Most of this agriculture is destined for drug trafficking. Photo: Sebastián Castañeda/Mongabay Latam

Since Bolsonaro became president, the progress of infrastructure projects in the Amazon has accelerated. "We are going to have a passage to the Pacific, where we will arrive by land,” said the president last October, giving the green light to the road from the Brazilian side. To these statements, the vice-governor of Ucayali, Ángel Gutiérrez, responded by telling the local media that "this was the moment for integration”. For Gutiérrez, the existing delays are due more to the national authorities' apathy toward what he considers an important project for the national economy. “But we are committed to put pressure, because otherwise we will continue with the same thing for 20 to 30 years,” he said.

The regional governor of Ucayali, Francisco Pezo Torres, has applied pressure since 2019. That year he signed, together with his counterpart from the Brazilian state of Acre, two declarations of interest for the Multimodal Interconnection of Pucallpa with Cruzeiro Do Sul. They also issued an ordinance declaring the air connection between the two cities to be of regional interest and created a technical secretariat for the cross-border integration. The interest in this project is such that in September 2020, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, Pezo Torres traveled to Cruzeiro Do Sul together with the regional governor of Madre de Dios, Luis Hidalgo Okimura, to meet with Brazilian ministers and the vice-governor of the state of Acre.

The pressure by regional authorities reached the Congress of the Republic. On October 19, three weeks after the meeting in Cruzeiro do Sul, César Gonzáles Tuanama, the congressman for Ucayali, presented a bill that seeks to declare that "the sustainable multimodal integration between Pucallpa and Cruzeiro do Sul” is a matter of public necessity and national interest.

Stories Without Borders asked Pezo Torres, Hidalgo and Gonzales about this project. Governor Hidalgo was the only one who did not respond.

Pezo Torres said in his project for the integration of Peru with Brazil, a highway is his third connection option. "My priority is air and rail,” he said. When asked who came up with the idea for the highway, Pezo Torres said it was "an interest of the Brazilians.”

"For a matter of speed, they want it to be a highway, but we see it as a threat,” Pezo Torres said. Pressed about whether the project had been presented to the indigenous people who would be affected - either with a highway or a railroad - the governor confirmed that it had not yet been discussed with them. "We want to wait for the treaty to reach the national level,” he said.

Congressman Gonzáles gave the same answer. "(Consultation with indigenous communities) is a technical issue. As a matter of time we are launching this bill because at a general level it is important for the development of the nation", the legislator said. What development are they referring to?

Most of the riverside communities along the Abujao are indigenous, both Shipiba and Asháninka. They have witnessed how the river and forest have changed,and fear this will intensify with the arrival of the highway. Photo: Sebastián Castañeda/Mongabay Latam

A road in the new coca emporium

"Why are you here? Nobody talks about coca here, it's very dangerous.” This phrase was repeated, in different words, in each community along the Abujao River that we visited for this report. Our travel through the area, which should have lasted four days, had to be reduced by half due to the arrival of outsiders in the communities we visited, who asked questions and demanded explanations about our presence in the area.

"It is better for you to leave because you may end up dead," warned the leader of one of the communities, who requested his name be omitted. He also feared that reprisals could later affect those living in the area.

As they stand in front of the river, the indigenous inhabitants of Abujao have observed how new people have been arriving, sometimes armed. They prefer to remain silent out of fear of reprisals.

Photo: Sebastián Castañeda/Mongabay Latam

Tension is a constant along the Abujao. That is why, although many residents want to denounce what is happening in the basin, no one can do so publicly out of fear of how the drug traffickers might react.

"If you don't disturb them, you'll be safe," says Edgar, a Shipibo indigenous resident who has lived in the area for more than 50 years. The change has been abrupt, he says, as they have gone from feeling free to living in a kind of prison and under constant surveillance. Nothing that happens in Abujao goes unnoticed by the settlers who have arrived in recent years. "They are the ones who have come to cut down the forest and plant coca. And they don't plant one hectare, but 20 to 50 hectares," says Ernesto, a Shipibo native.

This is why they repeatedly mention that they now live in the "New Vraem”. The Apurimac, Ene and Mantaro River Valley (Vraem) is the area with the highest production of illegal coca crops in Peru, where drug traffickers operate and have allied with terrorist remnants from Sendero Luminoso. It is also known as a liberated zone, where despite military and police operations, it has not been possible to completely eradicate illicit crops.

This is one of the spots in the Abujao with the largest number of acres deforested by coca, according to DEVIDA information as of 2019.

Image: Satellite map capture/SISCOD DEVIDA.

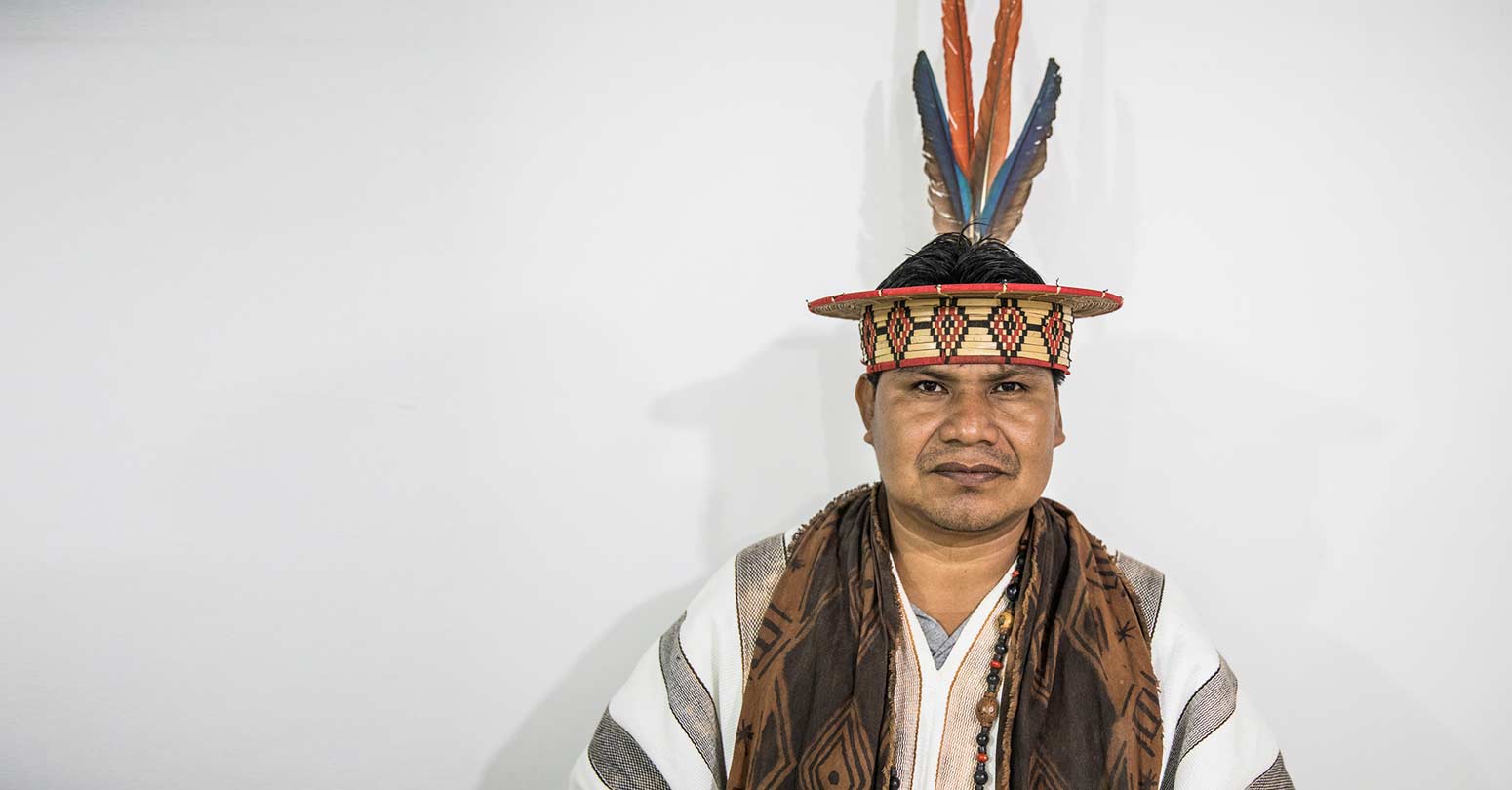

For the Asháninka leader Reyder Sebastián, the construction of the highway would bring even more chaos to the area, especially because, so far, indigenous people have not been consulted about the project. "We want to work with the State to see how we can find a better solution to connect our towns without harming them," says Pinkatsari native Sebastián. The Pinkatsari, as the great chiefs of his ethnic group are known, is concerned. Unlike the Shipibo community members on the Abujao River, he can speak more freely because he lives in the city of Pucallpa. Sebastián points out that he has denounced the insecurity along the Abujao River more than once, but the authorities do nothing. Even now, with the possibility of a highway in that area, they are being ignored. "They don't look at us as people with rights, but as objects," says the Pinkatsari.

The figures illustrate in black and white what Reyder Sebastián is saying. According DEVIDA, in the district of Callería, where the Abujao River is located, about 2,000 acres of illegal coca leaf crops were registered in 2019, slightly lower than the 2,450 acres in 2018, but still significantly high compared to the 700 acres that existed in 2016.

The Common Good Institute (IBC) has estimated that 30% of this total would be concentrated in the Abujao basin. "The reported findings illustrate that illegal coca leaf cultivation continues to be an important factor in deforestation in this area," says Pedro Tipula on behalf of the IBC. The geographic information systems specialist says this figure could easily have risen up to 35% by 2020. The map created by IBC for this report shows the presence of illegal crops on both sides of the route through which the highway would pass. According to both Tipula and Dávalos, these deforestation patches would tend to grow with the passage of this stretch of road.

In this figure, more layers have been added to show the pressures that the area of the proposed highway project is already under: forestry concessions, agricultural deforestation and coca patches. Surrounding it, there are protected areas. According to scientists consulted for this report, the construction of a highway would increase the deforestation. This map was prepared by the University of Richmond and the Common Good Institute at the request of Mongabay Latam.

The Peru-Brazil drug trafficking route

According to the collected testimonies, most of the planting and processing of the drug or cocaine paste is carried out by the settlers. However, there are Ashaninka and Shipibo natives who have plots of land with coca crops and sell their harvests to third parties, also known as 'outsiders.’

"It is done out of necessity. For example, in last year's pandemic we could not eat only from the corn and plantain we planted. It helped many of our brothers and sisters to survive," says Eduardo, an Ashaninka native.

In DEVIDA's last full monitoring report, published in 2018, the Abujao basin was already mentioned as a new area of coca expansion. The river was even considered one of the main routes for drug traffickers to bring drug to Cruzeiro Do Sul. These coca derivates came from nearby areas in Callería and even from Aguaytía. According to sources from the Peruvian National Police's Anti-Drug Directorate (Dirandro), the Abujao - Cruzeiro Do Sul route has been used for this purpose since at least the beginning of 2010.

The closer you get to the Brazilian border, the greater the danger. However, throughout the Abujao basin, the effects of drug trafficking and gold mining are felt.

"Every day we see the narcos pass through the community," says Juan, a Shipibo native who lives near the entrance to the Abujao River. "Sometimes they dock their boats to ask us for fish or to buy food and they pay us in dollars. We have to accept. But the situation is getting worse," he says.

This is the second largest deforestation point for illegal coca cultivation on the Abujao river. Image: Satellite map capture/SISCOD DEVIDA

"Sometimes we run into 'backpackers' who carry drugs to Brazil, or we go out hunting and we find a runway. If we hear the sound of the plane, it's better to get out of there. We are even afraid to find a maceration pit because we think they might harm us," says Edmundo, a Shipibo native. There is evidence of cocaine processing laboratories: in 2010, the police found six of them processing cocaine paste.

Bernabé, a motorcyclist who has recently traveled through Abujao with a team from the Regional Health Office, says that along the way they were constantly stopped for identification. "They only let us go through because we were a health brigade," he recounts. The sensation is the same: the indigenous people are now treated as strangers in their own territory.

That's why nobody wants to speak out loud. "Messing with them is complicated, just look at what happened to [indigenous leader Edwin] Chota. He complained a lot to the illegal loggers and they took him down. What guarantees do we have?" says Edmundo.

"Do you think that with the highway this situation will improve?" asks Pérez. "For example, in Satipo, where the road reaches, it has been useful for water and electricity to arrive, which is good. But the rest? I have seen nothing but poverty," he adds. According to Pérez, the road was used to remove natural resources more quickly and to promote the migration of people attracted by coca leaf cultivation. "They don't even have trees to build their houses.”

Many Shipibo and Ashaninka natives have had to confront the Covid-19 pandemic with natural medicine. The lack of medical attention from the capital of the region is due to the remote location as well as the danger of entering the area. Photo: Sebastián Castañeda/Mongabay Latam

A work too expensive for biodiversity

The projections that have been made since 2010 on the impact the highway would have do not paint an encouraging picture. The most recent study was published last year by the Conservation Strategy Fund (CSF), which developed an analysis of 75 road sections under construction in five Amazonian countries. In the Peruvian case, twelve were analyzed, including the Pucallpa-Cruzeiro Do Sul road. After evaluating economic, social and environmental variables, only six of the twelve were found to be profitable. The Pucallpa-Cruzeiro Do Sul highway is not one of them.

"The loss generated by the project would be $17 million. In addition, it would generate a deforestation of more than” 59,000 acres, the expert explains Alfonso Malky, CSF's technical director for Latin America.

The study recommends that in the case of the road projects that are economically unviable, it would be best to cancel them.

"Generating environmental impact and losing money at the same time is not the most advisable thing to do," the report states. For Malky, "these studies serve as a tool to measure project efficiency and, although it is not a recipe, it is an exercise that demonstrates the need for more comprehensive analysis. This should help governments improve their efficiency in terms of road investment.”

The Nature Conservancy's researcher, Luis Dávalos, points out that the impact of an 87-mile road will have an effect similar to that of the Inter-Oceanic Highway in Madre de Dios. "These effects could be brutal. Not only because, unlike the Inter-Oceanic Highway, here there is not even an open trail, but also because the entrance of a road in this forest would cause a transformation of productive activities," explains Dávalos.

This change in the territory is already happening right now, with the presence of drug trafficking and illegal mining, and the highway could become the engine of these activities.

The pandemic briefly paralyzed the departure and arrival of cargo ships. However, work has to continue. Fruits such as bananas are traded, but illegal products such as drugs are also transported on these rivers.

Photo: Sebastián Castañeda/Mongabay Latam

"The impact will be seen in deforestation. When a road is built, even if you have titled communities in the area, migration occurs. Villages and camps open up," says Víctor Manuel Hidalgo of the NGO Nature and Culture International (NCI). Hidalgo has been in the area for the past decade for another reason: the creation of a regional conservation area (RCA) named Alto Tamaya-Abujao. This area is located on the left bank of the Abujao River, and although the road runs on the right side, the effect on biodiversity is undeniable, explains the NCI specialist.

According to Hidalgo, if the construction of the new road is completed, "the migratory processes of the wildlife would be interrupted, especially those of climbers such as monkeys that are exposed to the risk of having to descend to the road to continue their journey through the forest.” According to the NCI specialist, a significant presence of wildlife has also been identified in the area. Even the largest feline in the Amazon, the jaguar, roams the forests. "The entire area is a natural corridor for the otorongo," he adds.

Hidalgo also highlights the wealth of trees that are currently endangered, such as tahuari (Tabebuia serratifolia), cedar (Cedrela odorata), mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) and shihuahuaco (Dipteryx sp.), species that are heavily exploited in the jungle. This abundance of resources is confirmed by Jorge Vela, a researcher at the National University of Ucayali, and by Nelson Seijas, Director of Conservation and Biological Diversity of the Regional Government of Ucayali.

Asháninka (Pinkatsari) leader Reyder Sebastián is one of the few who can speak out and denounce what is happening in the Abujao. Most prefer to speak anonymously. Photo: Sebastián Castañeda/Mongabay Latam

"It is an area of high biodiversity," Seijas told Stories Without Borders. However, he preferred not to express his opinion about the road proposal that the regional government is promoting. "It is a long-standing proposal and it is not yet known whether it will be a road or a railroad. The impacts will have to be determined through studies," he said.

But studies do exist. For example, David Salisbury of the University of Richmond points out that the projected highway would cross rivers and streams on the Peruvian side up to 17 times. "We know the impact of this type of construction from what has happened in other rural and border Amazonian areas, where deforestation, land trafficking, illegal looting of timber and illegal hunting of wildlife has increased," says Salisbury. "We have to see the area as a continuous ecosystem. Natural areas can no longer be seen as islands," adds Tipula of IBC.

The Shipibo and Ashaninka indigenous communities that would be affected by the road have not been considered in the discussions, says Berlin Diques, president of the Ucayali Aidesep Regional Organization (ORAU). "If we are aware of anything it is through the media. We know that this regional government has initiated coordination with Brazilian authorities, that the case has even been presented to Congress, but the indigenous communities have still not been consulted at all," the leader says.

The same problem is occurring in the Brazilian section of the road. Brazil's Federal Public Prosecutor's Office has initiated a civil investigation into irregularities detected in the highway construction plan, including the lack of free, prior and informed consultation.

At night, the river seems peaceful, but no one travels on it. There are armed people guarding the transfer of drugs being processed inside the forest.

Photo: Sebastián Castañeda/Mongabay Latam

Lissette Vásquez, head of the Environmental area of the People' s Ombudsman's Office, comments that they have sent documents to the Legislative Branch on several occasions highlighting the danger of promoting highways without adequate discussion and prior consultation. "People's rights can be put at risk. In addition, the fact of declaring it a project of public necessity cannot mean the exoneration of an integral evaluation,” concludes the official.

After the interview with the Ombudsman's Office this entity confirmed that an official letter was sent to the president of the Transportation and Communications Commission of the Congress to "warn with concern" about the impact this bill could cause.

Pérez says the majority of the Asháninka and Shipiba people do not agree with the highway construction, which is why they demand the immediate presence of the State in Abujao. "This area used to be quiet, but we have always lived with pressure on our necks. Twenty years ago, it was the loggers, then came the illegal miners and now the drug traffickers," says Pérez, recounting his experiences. "Now it will soon be the highway, and what about the population?"